The whimsical (and macabre) games of Madison Karrh

Video:

I was watching Day of the Devs during Summer Game Fest 2022, being absolutely blown away by the announced titles that all seemed to be right up my alley. There was Bear and Breakfast that I ended up playing on release; there was Animal Well that I still have no clue how to play properly; and, lastly, there was Birth. A game created by Madison Karrh, a solo developer, about living alone in a big city and then one day deciding to build yourself a partner from spare bones and organs to quell your loneliness.

I was intrigued beyond measure. Birth gave off strong Rusty Lake vibes, but at the same time it seemed to be very cozy and contemplative, not dangerous. Given my fascination with the macabre and largely morbid sense of humor, I did not doubt for a second that when Birth comes out, I'll pause every other game to play it.

However, there was still some time before its release, so I decided to look into Madison Karrh to see if there were any other games she developed prior to Birth. And there absolutely were! Whimsy was the first one among those available on Steam, published in 2019, and the second one is Landlord of the Woods, published in 2021. I played both of them, and then Birth when it came out, and today I thought it would be fun to take a little trip through the catalogue of Madison Karrh and see how her games evolved through time. I will supplement our journey with quotes from the episode of Unity Tales where she was a guest, and also from the interview "Dissecting Birth with Madison Karrh" by Jordan Oloman. All links will be in the description below, as usual.

We'll start with Whimsy, which takes about 30 minutes to complete; it is vital to our little analytical adventure. Yes, the controls are not as responsive as you'd probably expect, and moving through the scenes might not be graceful enough, but in Whimsy we can see the budding game structure and puzzle types that would not only be kept throughout the entire game catalogue, but also refined and reshaped.

Whimsy is a simple puzzle game that I can compare to a sectioned sketchbook; in her Unity Tales episode Madison Karrh shares that, being a solo developer, she had to learn how to draw and ended up just practicing every day from zero previous experience. Scenes in Whimsy are more like a small collection of items and/or a character or two against a simple backdrop. The scenes are united by a theme — you're in a forest — but that's it.

The structure of Whimsy, that will evolve later in Landlord or the Woods, and then in Birth, is represented by chapters, supported by a plot premise: in the forest, that has always (always always always always always) belonged to you, you find some blood red footprints, which prompts you to investigate. Every chapter consists of a few scenes where you need to complete all puzzles to proceed. There will be a character or two who will ask you to fetch something for them, and then they will let you through. Solving puzzles of the chapter results in you getting the desired item. Then you get a little bit of narration and arrive at the next bundle of scenes.

I personally like this type of structure for a puzzle game. Sometimes, if I am solving riddles in a bigger area, or unbound completely, it becomes overwhelming for me. Both Whimsy and Landlord of the Woods remind me of Cube Escape Rusty Lake games in this regard — which is not surprising because Madison lists Rusty Lake games among those that inspired her the most. It's easy to keep track of all the puzzles if you need to do them in a particular order, because in any given chapter there are just a few.

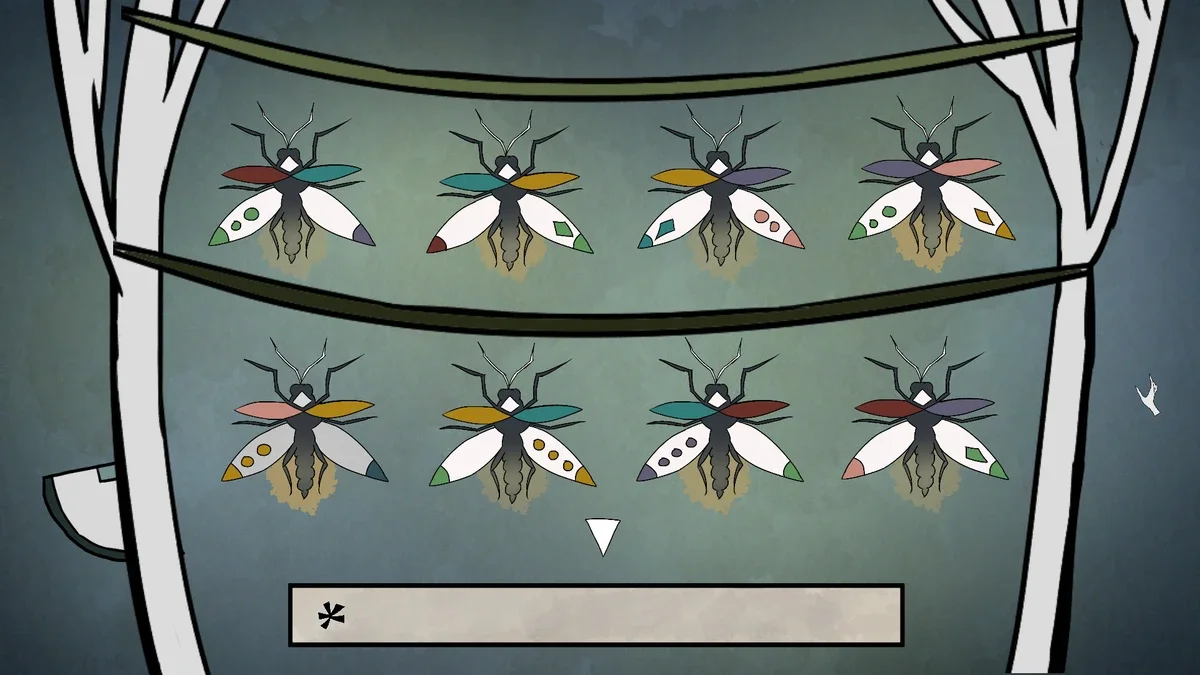

In Whimsy we can also notice the prevailing types of puzzles, which will be carried over into Landlord of the Woods, and ultimately into Birth. Luckily for me, none of my most disliked puzzle types are here (communicating vessels and square sliding puzzles). First of all, there are pattern puzzles, like assembling a picture from vertical panels, or stringing fireflies so that the neighboring wings are of the same color. Secondly, we have what I will refer to as "tactile puzzle", although the word "puzzle" might not be correct here. Be it just clicking on something to clear it off the surface, or clicking on something to reveal an object inside, these "puzzles" do not require much intellectual effort, and I LOVE it. I think it hugely benefits the pacing of the game, so that you're not just solving puzzles back to back to back, and I also find it very therapeutic and relaxing. It's much like playing in the sand or with another tactile medium when you're a kid: you just mess around and move on. These types of puzzles — pattern-based and then tactile — will be present throughout the entire catalogue and will evolve in the most amazing ways.

Similarly, in Whimsy we can also see the types of puzzles that largely stayed within Whimsy. There is one rather obscure puzzle where you need to notice some clues in the previous scene, and then use them in a door lock puzzle to get in. In my opinion, this is the least clear puzzle in Whimsy, because you just skip through to the door itself and then wonder where you're supposed to get the information required. This type of puzzle will return only in Birth, and I think only once, and it will be done much more gracefully there; the player will have multiple opportunities to come across a clue and then start looking for similar ones with purpose.

Another type that didn't get a lot of traction throughout the subsequent titles, is the "figure out the number" puzzle. In Whimsy there is a code locked door that you need a password for, and later on you find a book with a few codes and corresponding comments about how only one or two numbers are correct, and whether or not they are in their place, but with no indication of what the numbers the note is talking about. By reading all comments to all codes, and comparing them, you're supposed to figure out the password. While it might be interesting for some players, this type of puzzle leaves me absolutely indifferent (like most puzzles that have to do with numbers), and in Whimsy it stood out like a more "traditional" puzzle. Puzzles with codes or numbers will come back later, but they will be less intense, more whimsical and will just generally fall in line with the author's style.

The journey through the forest ends with the words "You are miniscule in the very best way" which might sound rather cryptic, but it's just our first glimpse into the philosophy behind these games, and we will see more of it in subsequent titles.

Moving on to Landlord of the Woods — the game I genuinely love and would recommend to anyone. It has a much stronger plot premise that nicely frames the chapter-based structure of the game that we are already familiar with. You're in your mid-twenties, and you feel like you're wasting your life. One day bleeds into the next, and you wonder if this is all life has to offer. Deeply unsatisfied with your job and your daily routines, you apply for a new job: to be the landlord of the woods.

Madison describes her games as semi-autobiographical, and you can really feel it in Landlord of the Woods. That is why, I think, it is so relatable. I've certainly been there in my early- to mid- twenties, and the game made me reflect on that period of my life. It's much easier to open up — even if to yourself — when someone opens up to you through a piece of media of their creation.

In the intro we can see that the artstyle changed significantly compared to Whimsy: it is more coherent, there are more details, and the scenes have much more variety. The overall color palette also changed and has more nuance now.

However, Landlord of the Woods remains to be as whimsical as Whimsy was, as we can see from our "Tasks for today" list that includes organizing the bugs and aligning the tools. Present in Whimsy too, the running theme of bugs, viscera and decay continues in this game as well, retaining its light-hearted, matter-of-fact tone that will make you accustomed to it, even if your initial reaction is one of skepticism or disgust.

Landlord of the Woods introduces physics into the game environments, and the way you interact with objects changes significantly compared to Whimsy, where you could basically just drag and drop, or click. Here you can make a mess by pouring things, turning them upside down, moving objects on the shelves by dragging one and seeing how it impacts others. I see it as an evolution of those puzzles that are not really puzzles, we talked about in Whimsy: you can interact with the environment now without any intent to achieve anything or solve anything: just to have fun and make a mess. This physics-based world interactivity will evolve into something even more exciting in Birth, just you wait. In Landlord of the Woods, you still need to click on stuff.

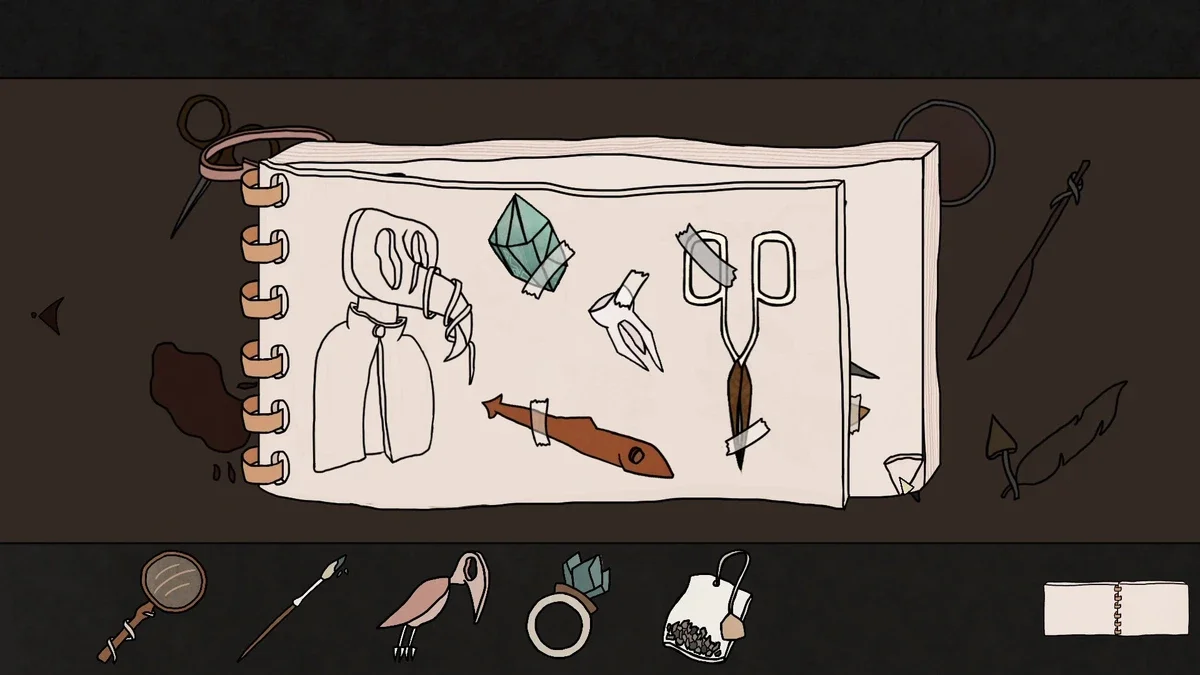

After spending some time on your routines that you explore through what feels like a collection of demos for each puzzle type, you get a letter in the mail saying that you got the job! You are the Landlord of the Woods now, and your main responsibility is collecting rent from each resident of the woods. You get a special notebook that lists all tenants and also all items you're supposed to collect from them, and you go off into the woods to meet new people.

Here the game falls into the chapter-like structure we have seen in Whimsy, only now it is much better defined and framed by the plot. Each resident you visit is a chapter, and within each chapter you have a few scenes with puzzles you're supposed to complete. The game is still linear, meaning that you cannot jump between tenants and can only proceed to the next one after you've collected the rent from the current one.

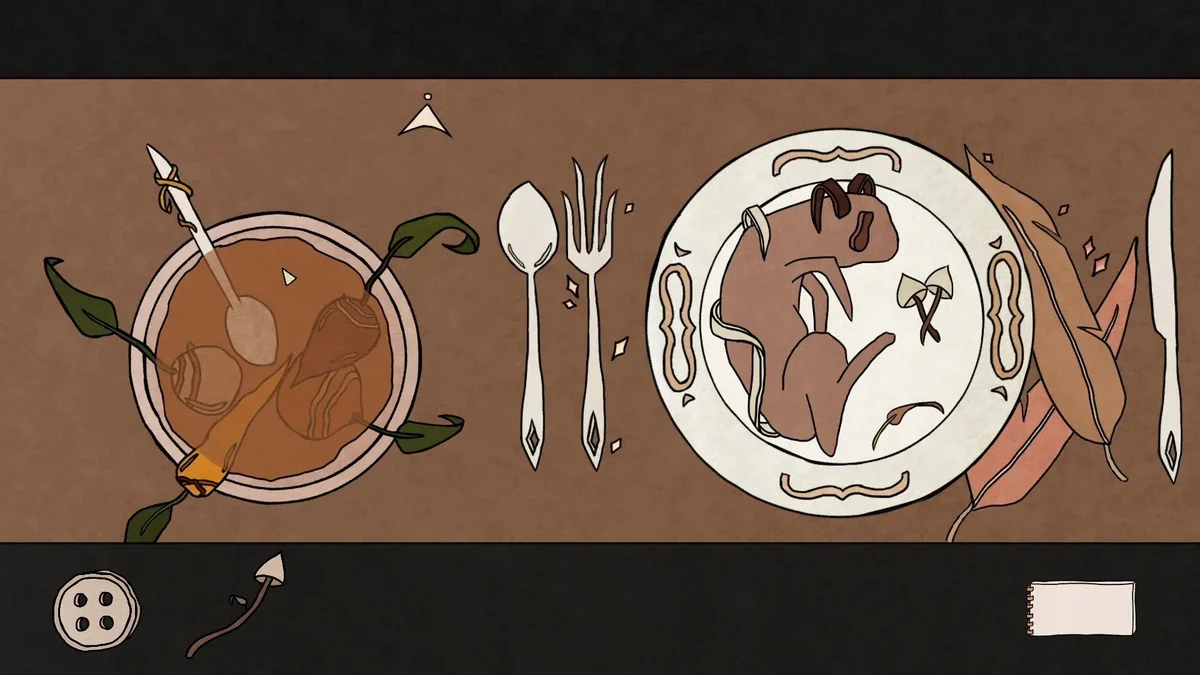

The inhabitants of the woods have weird lease contracts that state the conditions under which they pay rent. One tenant only pays rent after they are fed a meal. Another only pays rent after the trees in their yard are "decorated in a spectacular fashion". These are small individual stories within a bigger one, and your job is to solve a few puzzles to fulfil the condition of their lease and then receive the payment.

Landlord of the Woods also incorporates a little bit of a "hidden object" gameplay as some of the items you're supposed to receive as payment are not necessarily hidden behind puzzles, but are just lying around among mushrooms, branches and bird bones.

The game ditches more traditional multi-step puzzles entirely and leans into the style already established in Whimsy: pattern- or shape-based puzzles, some of them inherited directly from Whimsy, and new movement or physics-based puzzles like stitching up a bird's body. There is also one unique puzzle that you can't fail: one of the tenants asks you to redecorate his living space, and you spend some time moving furniture and putting up shelves.

Landlord of the Woods leans heavily into the macabre themes and aesthetic as you spend time messing with people's insides, boiling brains, sifting through bones and collecting hearts. I, however, hesitate to call the game scary or gruesome; despite its focus on one's inside world, death and decay, it is conveyed in such a simple manner that it becomes mundane. Just the way things are. I think this is one of the stark differences (among others) between the games of Madison Karrh and Rusty Lake games. Rusty Lake also loves macabre stuff, but the tone is completely different: it's more of a thriller, when Landlord of the Woods and Birth are basically slice-of-life. Absolutely fascinating.

I won't spoil the ending of Landlord of the Woods, but I find it superb and would encourage you to give this game a try. It is also about 30 minutes long, just like Whimsy, but it is much, much smoother, and thus appears longer than it is. In Whimsy, I feel, some time is spent just orienting yourself in this bizarre world and figuring things out, stumbling around. Landlord of the Woods is a small but complete experience that flows very naturally and has a clear three-act structure plot-wise.

And now we arrive at our last stop — for this post, at least — which is Birth, released in 2023. The description of the game is as follows, "You are alone. You will build a creature, a partner, a wet warm heart, a collection of bones."

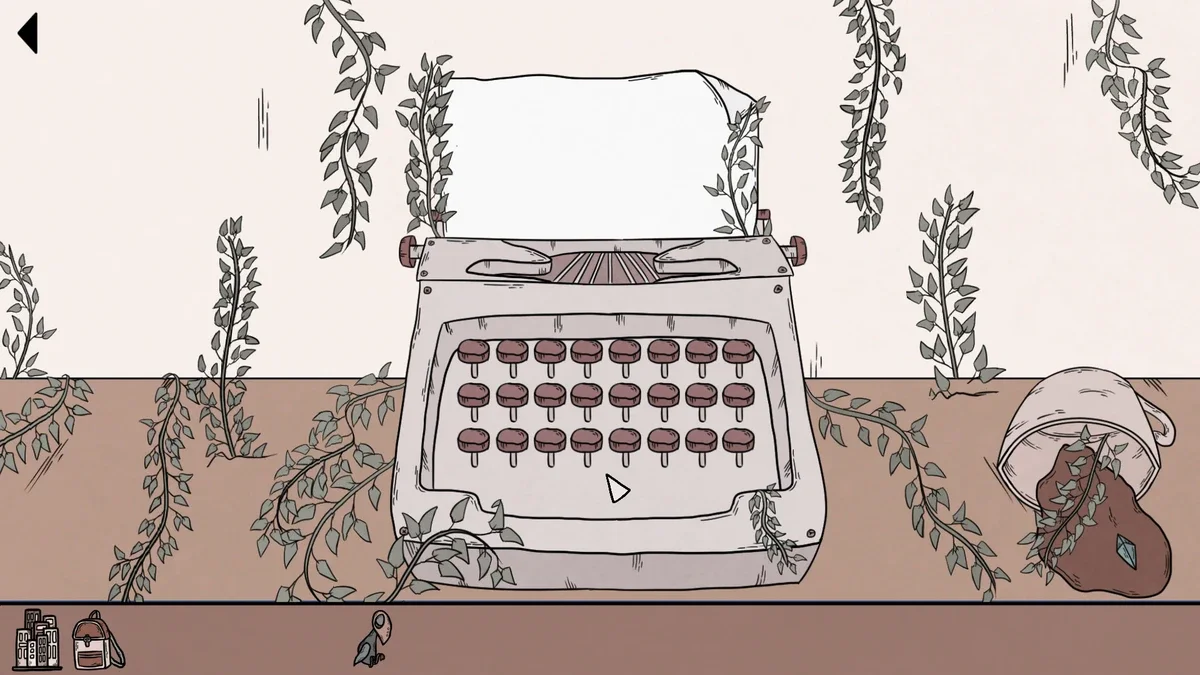

In Birth you live alone in a big city and one day decide to create a partner for yourself. While traversing the city, you collect bones and organs for this very task. Much like Landlord of the Woods, Birth has an intro, and you even create a character. The character creation screen is similar to the one you have in Landlord, but more polished and has a few more options. While exploring your own apartment and getting the hang of things, you stumble upon a major evolution of the physics-based interactions with environment, introduced in Landlord of the Woods.

You don't need to click for certain interactions anymore. It's just enough to swipe your cursor along a garland of light bulbs to make them move around. I never expected such a seemingly simple thing to add so much joy to my exploration, but all I wanted to do in Birth was just to point my cursor at every single thing and see if it moves around. There are endless little things that use this mechanic: from dangly things to flowers opening and closing their petals. And it's also used in solving puzzles, of course.

The artstyle evolved further: patterns are more intricate, details are in abundance but not overwhelming the scenes, and the color scheme is more consistent, while the general mood and whimsical style stayed the same. The UI is far more elegant, and if we remember Whimsy, the difference is night and day. Navigating the city is really easy and straightforward despite the fact that spatially it's become more complex.

The chapter-based structure here evolved into not an open-world, but an open-area: the city you're exploring is divided into three big parts — we'll call them "chapters", but within each chapter there is a number of smaller self-sufficient puzzle areas that you can explore in whatever order. For example, in the first chapter there is an apothecary, a bakery and a coffee shop, each place a separate collection of scenes and puzzles that will result in you getting either a bone or an organ for your very important DIY project. You can explore those places in any order, and when you are done, another part of the city will become accessible.

Birth further embraces the bone-and-viscera aesthetic, but again, much like Landlord of the Woods, does it in a very slice-of-life way that is not off-putting at all. What's even more interesting, in Birth exploring other people's apartments and peeking into their daily lives becomes a strong point of focus. I find it very interesting, and also very human. I think it's natural to wonder about other people and what they do and perhaps compare them to yourself. Have you ever looked at someone on the street or in a cafe, and asked yourself, what's on this person's mind? What do they do for a living? Do they have a family? A pet? What does their place look like?

In the Unity Tales episode, Madison says that "the desire to know people's daily lives is really inspiring". Birth focuses on the interesting found in the mundane. It's just one random day of city life: there is absolutely nothing out of the ordinary happening on the streets, or in the shops. It's one of the plainest days, and yet, the exploration of every space is thrilling. Partly because many puzzles produce unexpected results — you might be familiar with this 'subverting expectation' trick that Rusty Lake loves to do. There, you plant a seed, and you expect a plant of some sort, but get a shrimp. Here, someone is holding a lollipop, and when you unravel it, it's an eyeball. Good thing you found it!

And partly, because there is beauty in the seemingly unexciting everyday life, and exploring the city makes you reflect on the same spaces you visit in your day-to-day. "I think most of life is made up of mundane moments, so maybe those are the most important pieces to document", says Madison in her interview "Dissecting Birth", and I tend to agree.

Birth also has something that the two earlier games lack: additional stuff to do that does not necessarily move your main quest forward. Throughout the city you may find coins that you can use in a variety of situations, from a capsule-toy vending machine, to a pipe, to a mail box, and get some curious results. This is a big leap forward from the previous games: free exploration unbound from your quest goals done on a small scale.

Birth explores both loneliness in a big city, especially when you first move and are uprooted from your environment and also building connections with other humans. You still yearn for someone else, that is why you decide to build them for yourself. I think Birth perfectly captures the feeling of stepping out into the new neighborhood and exploring it for the first time. I've moved quite a few times throughout my life, and I know this feeling very well. How you step out of your new place — not quite yours yet — and just walk around the block. It's all very awkward. You see a cafe, or a bar, and you wonder what kind of people frequent it. Maybe, you can join them too someday? Or maybe not? Are there friends to be made? Birth is full of cautious optimism that many of us have when settling into a new place, and I think it's beautiful and also quite rare to see depicted in such a genuine, vulnerable way.

In "Dissecting Birth" Madison shares that initially the players were supposed to gather personality traits as well as bones and organs, but ultimately, she decided to let go of this idea, because she wanted to tell the story using as few words as possible. Birth is almost 4 times the length of Landlord of the Woods, but I'd say it uses much fewer words, and this style of storytelling suits the mood of the game perfectly. None of the puzzles are explained to you, but then again, they don't really need to be explained. Birth trusts the player to figure everything out on their own, and it works.

Birth (just like Landlord of the Woods before it) ends with the words "Thank you for taking a small amount of your allotted time on this earth to play this game’, which demonstrates a very important part of these games' philosophy. Yes, they often ponder death and also don't shy away from depicting it, but I think this ever-present idea of mortality highlights intentionality of existence. Our lives will inevitably end — and it's fine — so we need to pay more attention to how we choose to spend whatever time we have until that happens. I've been thinking more and more about it lately, and maybe it's just my old age getting to me, but I sort of regret a little bit lacking this realization when I was younger.

I highly recommend Madison Karrh's games. I feel like it's a very rare opportunity to follow a solo developer throughout multiple projects and see the evolution of their craft. I'd also recommend watching her Unity Tales episode where she talks about being inspired by both Frog Detective (that I can't recommend enough) and Rusty Lake, as games created by small teams. At that point she realized that you can just make stuff on your own and show it to people, which I think is a very important message to all people engaged in creative endeavors. Even if you are not a videogame dev, nor you seek to become one, I still recommend watching the episode; it's very inspiring. All links will be in the description box below. As far as we know, she is currently working on a new game, and I can't wait!

As usual, stay tuned here and on the Lair's YouTube channel not to miss out on anything.

Thank you very much for your time. Take care.