Have we lost patience for slow-paced games?

Video:

I learned about Harold Halibut when it released, unlike many people who had been following this incredible project for years, or maybe even a decade. I think, it was a part of a Steam Fest as a demo, but I managed to successfully skip it even there. I didn't know anything about the game at all and I didn't have ANY expectations which, honestly, ended up being and advantage.

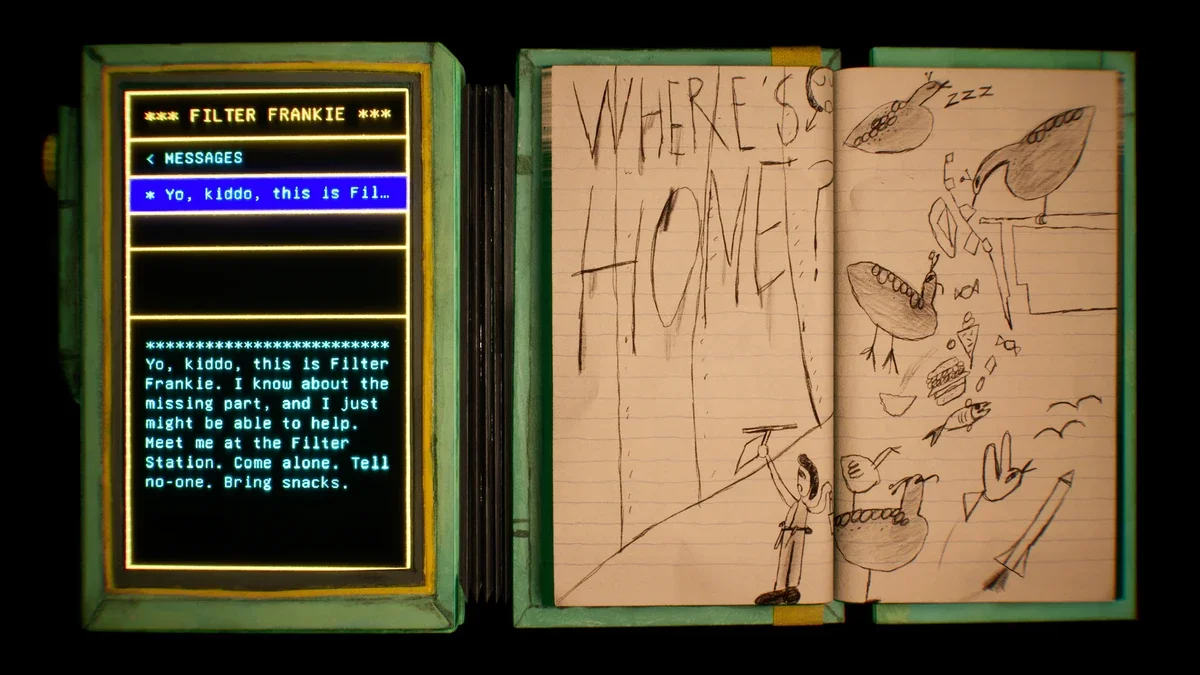

Harold Halibut was developed by Slow Bros., a small indie studio based in Germany. It started in 2012 as an expression of love for storytelling and stop-motion films; every little thing in Harold Halibut, along with the characters and the sets, was built, sculpted, or otherwise created in real life and then 3D-scanned. This is what strikes you first when you start playing Harold Halibut: the overwhelming tactile aspect to everything you encounter, down to the tiniest details. It's all real textures that you know: metal, paper, different types of cloth, wood, and it's truly remarkable to see it in a game like this. Simultaneously, you can see that everything is handmade, and with a great skill too. My favorite are probably the books, the brochures and other "printed" materials with handwritten fonts.

Also, the style of animation allowed the developers to do some incredible things that are rarely seen in other games: for example, when a character gave Harold a small bottle, I both saw that character holding it in his hand, and then Harold correctly accepting it and holding it in his hand. Honestly? Blew my mind. I am so used to characters just handing each other air in their clenched fists, because it's so difficult and inefficient to do a separate animation for each time someone gives or receives something that it is almost never done. And Harold is full of it. When you try to skip a dialogue, the game doesn't just do a cut, but it speeds up the animation because it is unique to every piece of dialogue.

Let me give you a brief overview of the story: you play as Harold Halibut, a young man living aboard an ark ship called "FEDORA I". In the 1970s, amidst the Cold War, some people on Earth figured that the world was doomed and decided to build a spaceship to leave the planet and search for another one. With both private and government funding, they managed to embark on an interstellar voyage. As they searched for another habitable planet, they accumulated a lot of knowledge and precious resources (like energy-producing bacteria) that allowed them to fully sustain FEDORA I and its inhabitants. However, a solar flare brought FEDORA's journey to an abrupt end, and it crashed on an ocean planet. 250 years have passed since FEDORA I took off from the Earth, and it's been decades since it sunk on a distant inhospitable planet. People have been trying to live their normal human lives aboard the Fedora, and many have already come to terms with the fact that they'll never fly anywhere ever again. But not Jeanne Moreaux, Fedora's lead scientist who's been taking care of Harold since he was a kid. She still harbors hope that Fedora will see the stars and continue its mission.

Seems like a unique story, doesn't it? I played through about a third of the game when I decided to see what the general response was. To my surprise, I discovered that Harold Halibut was just "Mostly Positive" on Steam (as I am writing this, it's "Very Positive"). I genuinely could not understand why so I dived into the reviews to see.

Most of the negative reviews mentioned either of these things or both: Harold Halibut doesn't have any real gameplay, and it's way too slow.

Let's start with Harold Halibut having barely any gameplay to it. It's true! This game is basically a walking simulator, where you walk from point A to point B, do a whole lot of talking, fetch quests and occasionally tiny tactile puzzles that are very basic by the true puzzle games' standards. You just watch the story unfold. The problem is that Harold Halibut was never — as far as I am aware — marketed as anything BUT what it is. Judging by the reviews, many players expected puzzles, inventory, point-n-click gameplay for no other reason than the game just sort of looking like a point and click adventure. Obviously, there isn't anything wrong with people wanting more gameplay in their games, but at the same time it's not like Harold Halibut overpromised and underdelivered. I found this divide between expectations and the reality to be very curious: it's almost how people often assume the game is "indie" just because of how it looks. As I've already mentioned, I had zero expectations, and it allowed me to just accept whatever the game was. Usually, I also like more gameplay in my games, but by the time I realized that there wasn’t going to be much gameplay beyond what I had already seen, I had grown quite fond of the characters and of Harold himself, so not having to solve progressively more challenging puzzles every ten minutes or do stealth sequences didn't really matter to me that much.

The second major complaint that permeated almost every single negative review I read on Steam and beyond, was that Harold Halibut is very slow, and thus poorly paced. The calm, measured tone of the game taking the player through the mundane Harold's day-to-day didn't seem to agree with many people who expected more action.

Being able to understand both of these complaints but not really relating to them myself, I thought, "is it possible that in the year 2024 we just don't have patience for slower games anymore?"

I played through the entirety of Harold Halibut, and I must say that for the type of game that it is, and for the story it's telling, it is wonderfully paced; it's simply perfect, and it would not work any other way.

I'll keep it as spoiler-free as I can; for the most part I just want to defend slow-paced games, I guess :D

Let's start with our protagonist Harold: not only is he a scientist's assistant but also a handyman, a repair man and all around a Jack of all trades but honestly, master of none, which, believe it or not, is a big point of contemplation for him. It's important to keep in mind that Harold was born after the Fedora crashed, and, consequently, spent his entire life on the sunken ark. It's not uncommon to see people noticing that Harold seems to be quite indifferent to whatever is happening around him, as if he is bored by his surroundings, and it's absolutely true. His whole life, for decades, he wandered the same corridors, entered and exited the same rooms, talked to the same people. Fedora is big, but not big enough for a person to be born, live their whole life and die on it, even though many generations of Fedorans did.

I think it's a good time to mention that in this game the measure of progression is not levelling up, getting to progressively more complex puzzles or gathering high-level gear (there is no gear). It's how much you've learned about the characters and how far you progressed through the story.

While searching for reviews, I found this really interesting feature on RockPaperShotgun written by Katharine Castle. The feature is based on Katharine playing an early preview build of Harold Halibut, and as far as I can say, she didn't like the game whatsoever — mostly because of Harold and his character. It's perfectly fine; sometimes you dislike the protagonist of the game for whatever reason, it happens. However, what seemed much more interesting to me, was the fact that on a couple of occasions she mentioned how she found the simplicity of the game's puzzles and quests insulting and disrespectful to her time.

In fact, the tasks Harold's assigned in the opening few hours of the game are almost insultingly easy, extending to little more than 'feed the fish' and 'talk to so and so', all of which can usually be accomplished by interacting with a single button prompt to move the story along.

Sure, feeding the fish in the first chapter doesn't require anything that advanced (although you do need to go and fetch the fish food), but I think that's because Harold has been doing it for years now. You're introduced into his simple everyday routines. It would really surprise me if feeding the fish involved some sort of a complicated puzzle.

Then Katharine describes one of my favorite episodes in the first chapter of Harold Halibut: Cyrus, another scientist on Fedora, asks Harold to see if he could fix his 3D printer that for some reason stopped working. You have a little puzzle where you unscrew a whole lot of screws clearing your way to a faulty wire and a button. As soon as you touch it, Harold gets zapped, and Cyrus is elated: it's hilarious to him. The printer wasn't even broken.

This is really sucky, not just because Harold's once again the butt of everyone's jokes, but because it also disrespects your time as a player. Puzzles should exist to further a game's plot, not just kill dead space between tasks for a laugh at your own expense.

This is by far the most curious passage of the entire feature to me. "Puzzles should exist to further a game's plot". Seems like a very technical, formulaic approach to a piece of entertainment, doesn't it? I have to admit, I myself get really upset when something that I do in-game doesn't have apparent reasoning behind it. Not necessarily because it was a waste of time, but mostly because I just like things to exist for a reason. This particular episode, however, is not completely useless and it's not there just to kill "dead space". It is to show you, the player, what kind of person Cyrus actually is. This "joke" says a lot about him, doesn't it? And in terms of this game's progression, you’ve just progressed a fair bit in your understanding of this particular character. It also provides context about Harold and Cyrus' pre-existing relationships. I doubt it was in the early preview build, but later you'll have a chance to watch Cyrus play the exact same joke on another person again, just for the giggles, which shows that it's not really Harold specifically being "the butt of everyone's jokes"; Cyrus is just the way he is with everyone on Fedora.

I found Harold as a character to be really endearing and very relatable, at least to an introvert like me. He struggles to build meaningful connections with other people but is always ready to help, even if every time there's a bit of anxiety he might not be able to do his best. Harold is kind-hearted and has a fine sense of humor; prejudices seem to not exist for him. He treats everybody with respect and attention, never dismissing concerns that someone shares with him. At the same time, he is barely an adult, and as many people in this tender age he wonders if there is more to life. The options on the sunken Fedora that is not likely to fly anywhere ever again are quite limited, but he still wonders and dreams.

Simultaneously, Harold, like many people stuck on the ark, tries to find the meaning of "home". Is Fedora home? Should the Fedorans strive to return to Earth, the home of their ancestors, even though they've been stranded in space for generations and there isn't even a single person who could tell them about living on Earth firsthand? Maybe, "home" is something you find after a life-long search; should Fedora continue her interstellar journey to find a new planet they could call home? Could it be that "home" is not a place, but someone? Could it be that "home" is something you carry with you?

The game explores the nuances of being a human in a way that is rarely done; with a protagonist stuck in the circumstances he never chose for himself, struggling with wanting to belong yet doubting he would ever be able to fit in anywhere. It is about friendship, community, anxiety, hope and loss. In a way, it is a coming-of-age story because being an adult is about making your own decisions and being responsible for them. And I love it for that, just as I loved Night in the Woods years ago.

It's a good few in-game days of you watching Harold live his usual ordinary life where the events of note are something along the lines of "someone put a graffiti on the wall" or "AllWater company raised the ticket prices again" before something actually happens. Among the reviews I read a few that suggested cutting out some of these chapters to jump to the exciting stuff sooner. I don't think it is a great idea, even though it might seem like it. "The exciting stuff" is made exciting also by the power of contrast. By skipping most of the Harold's day-to-day chores you'd just devalue the events that transpire further, and Harold's reaction would seem disproportionate; I don't even think we would be able to understand his decisions, when the time for him comes — for the first time ever — to actually decide something for himself.

Also, Harold Halibut is a game about humans on a stranded spaceship. It's about a close-knit community of people with their hopes, and dreams, and strengths, and weaknesses. The more you interact with them, the deeper your connection grows. Just like in real life: making friends takes time. Interestingly, the starting point is never zero: Harold has pre-existing relationships with all Fedorans, and you'll be watching him navigating his social life in many different ways. The hours that you spend on Fedora talking to people, helping them, crying and laughing with them, make the payoff at the end so much more emotionally touching. It is certainly an investment of time, but it's definitely not a waste.

There is a scene — an absolutely soul-wrenching scene — towards the end of Harold Halibut that I felt was this big payoff. And while I was overwhelmed with emotions, I thought — this is it. This is what it all was for. I would have never ever felt even remotely this way had the game not been as slow and thorough with character development and exploration as it had been up to this point. All of that was for this moment. And even though soul-wrenching — it also felt cathartic. It was great.

All of the above leads us to the question, "Are slow-paced games poorly paced games"? I think, the answer to it is quite obvious: no, they are not. Some games only ever work if they are slow, and I feel like Harold Halibut is a perfect example of that. Following the launch of Harold, I just kept thinking: has our patience for slower paced games decreased over time? How the games that I've loved for years would fare on the current gaming scene? It might sound weird, but I think Night in the Woods, one of my favorite games of all time, is quite close in nature to Harold Halibut. It was released in 2017, quite some time ago, and there you also mostly just run around talking to people. In Night in the Woods you have no inventory. You don't really do puzzles there except for occasional pretzel stealing. Yes, there is an optional rhythm game and a whole hack-and-slash game inside Mae's laptop but those are not in the main gameplay loop. Or let's take Kentucky Route Zero, which to this day is the most bizarre game I've played. The first episode of Kentucky was released in 2013, and it also doesn't have much gameplay as you just watch the story unfold.

Harold Halibut is undoubtedly one of the highlights of this year for me. At times it was heartbreaking, but I feel a little bit more human after playing it. If you are ever in a mood for a wonderful slow-paced game that you can play little by little, with no rush — give Harold Halibut a try. And if you have already tried it, I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. Do you think slower-paced games have fallen out of favor with the contemporary gamer?

As usual, stay tuned here and on the Lair's YouTube channel not to miss out on anything.

Thank you very much for your time. Take care.