The pacing problems of OMORI

Video:

I have never even heard of OMORI up until it was released and started popping up everywhere. People often called it "the second coming of Undertale" and this statement filled me with skepticism, not because I think that Undertale is the one and only game that nothing else can compare to (yes), but rather because OMORI's concept seemed entirely different to me, and I couldn't see anything these two games would have in common.

Later I learned that OMORI had been in development for 6.5 years after it was successfully funded on Kickstarter in 2014. It was planned to release a year after, then got pushed away to 2019 but still didn't make it. Finally, it was released on December 25, 2020 by OMOCAT. The game is based on a Tumblr webcomic omori ひきこもり [hikikomori]. OMORI was planned to be a graphic novel, but then changed its medium.

SPOILER WARNING

In this post I will discuss the premise of the game and the events that occur during its first section, about an hour or so. I will not, however, discuss the story itself, so you can read this post and still play the game largely unspoiled. I'll focus more on the pacing of OMORI, rather than on character and events.

Pacing and Structure

Sources: Pacing - How Games Keep Things Exciting by Extra Credits, Keeping players Interested - Pacing in Game Design by Brackeys and How to Keep Players Engaged (Without Being Evil) by Game Maker's Toolkit.

Think about the last game that you just couldn't stop playing. Why was it so engrossing? Did it have a good story-gameplay balance? Did it tease you with mysteries? Did it give you the necessary level of freedom to shape your own experience?

Now think about the last game you dropped halfway through or maybe even after the first hour. Why was it unable to engage you? Was it just not your cup of tea in terms of the subject of the story or genre, or was it something else?

Pacing and structure are crucial for engaging a player and leading them onward. There are many components that make up pacing and structure but don't worry, you already know them all and experienced them many, many times.

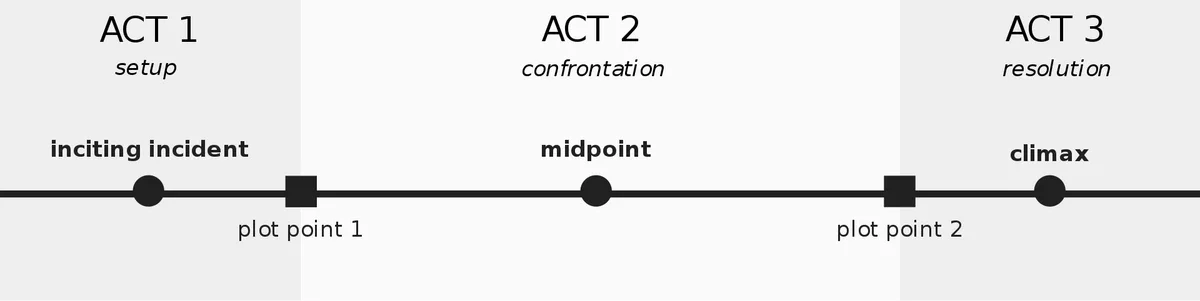

Almost any story - and almost any game for that matter - has a three-act structure in some shape or form. There are creators that despise the three act structure and they usually go on creating their own models of narrative but today we'll discuss a more standard approach. Let's talk about Setup, Confrontation and Resolution.

Setup

Setup is basically an introduction. Its main purpose is to pull you in and get you invested into whatever is happening. In games it is usually also a tutorial section that teaches you basic mechanics so you know what you're going to be doing for the most part of the game. This is also the stage where you are given enough story to get you interested and wondering what comes next.

A good setup is basically priceless because if it fails - the player will just quit and never come back, but if it succeeds to whatever degree, the player will get enough of an impulse to carry them further into the story. Of course, there are many genre-specific ways to craft a cool setup and weave a tutorial into it.

Setup usually includes something called an Inciting Incident or a Catalyst - an unusual event that grasps your attention and introduces the main conflict that the main character(s) will attempt to resolve.

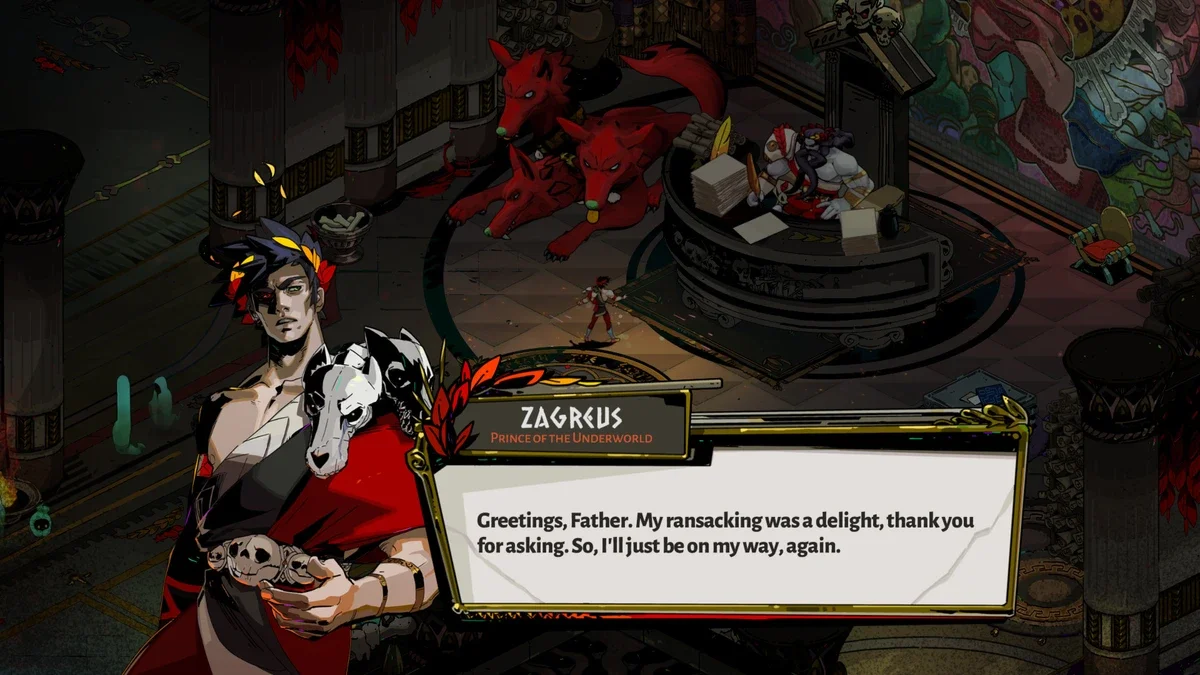

A good example of a brilliant setup is Hades. You are shown a short intro so you learn what the setting is, then you are introduced to the main conflict between Hades and his disobedient son Zagreus. You start asking yourself: what is the conflict? Why are their relationships like this?..

Then you are thrown into your first run where you learn your three attacks and the concept of boons. You proceed through Tartarus while listening to Zagreus and then inevitably die to return the House of Hades where you can meet a bunch of new characters and start exploring both the story and more of the game mechanics as you are getting ready for your subsequent runs.

The beginning of Hades pulls you in immediately by explaining enough of the world so you don't get confused and at the same time creating a mystery that intrigues you. From the gameplay standpoint, during your first run the game shows you your basic moves (your Attack, Special and Cast) and introduces you to a few boons so you are not overwhelmed, but at the same time lets you know that it's just a fraction of what you can experience in your next runs.

The inciting incident here is Zagreus' first attempt to escape from his father's realm and reach the surface. It introduces the main conflict: their relationships are bad, and for some reason the Prince wants out.

Hollow Knight has a very different kind of setup that still works perfectly because of its incredible timings. You are shown a short cinematic that doesn't really do anything other than introduce you to your main character, and then you immediately get control of the Knight who has just fallen somewhere from above. You have absolutely no idea what your objective is, where you are supposed to go and what you are supposed to do.

However, King's Pass is very linear at this stage of the game. While you are exploring the area because you have nothing else to do, the game teaches you its basic mechanics: jumps and attacks. It also introduces you to possible environmental dangers as you see a stalactite that kills one of the vengeflies. King's Pass has small platforming sections and small fighting sections to keep the pace of your exploration varied. It also shows you that there are places you can't explore yet, and this foreshadowing creates anticipation. You realize that in time you will be able to jump higher and somehow farther, and it's very exciting.

King's Pass is just long enough to show you a demo-version of the whole game so you know that you are going to be a) fighting b) platforming c) coming back, but not so long that you are completely disoriented and subsequently become frustrated. King's Pass inevitably leads you to Dirtmouth where you meet a few NPCs, get your bearings, learn about the mysteries of Hallownest, and then the game begins in earnest.

Here the inciting incident is the information that you receive from Elderbug about the lost kingdom of Hallownest below the town and the travellers that go down and never come back. It introduces you to the main conflict - something is happening in there, and you might learn more about yourself if you venture below and explore the desolate lands.

Confrontation

Confrontation is about the development of the main conflict, raising stakes, trying to resolve the main conflict (unsuccessfully) and uncovering more of the story and gameplay mechanics. At this stage the rhythm of the game is really important, aka how well the game balances tension and release.

Quite contrary to popular belief, good pacing doesn't go up in a straight line once the setup is over; it has peaks and valleys that keep the player engaged without exhausting them. Keeping the tension for too long without release makes the player, well, tense, and it can either cause stress or desensitization. Think about horror games that scare you all the time to the point that you can't be scared anymore. Or the games that have fights so long that you either become stressed out or no longer care and lose concentration.

At the same time, long periods of "release" or more relaxing parts of gameplay can easily make players bored and disengaged. The balance between intense sections that require player's attention, concentration and, possibly, reaction speed and calmer section of the game where the player can take respite, explore, learn more of the story, is quite difficult to strike but it is the very thing that makes games extraordinary.

Of course, there is a big difference between linear games that have to execute this balance all by themselves, and non-linear games that provide the player with things to do and delegate the pacing balance almost entirely to them. Think about INSIDE, one of my favourite games of all times that is beautifully structured and leads you forward through tight chase sequences (tension) and puzzle sections (release). And on the other side of the continuum we have such games as Witcher 3 and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild where you can move however fast or however slow through the main quest and regulate your own gameplay loop to your liking. If you don't feel like doing the main quest, you can do sidequests, if you're tired of that - play gwent, go treasure hunting, scout the area for koroks or go farming parts for your next fairy upgrade.

Resolution

The last stage is Resolution. Here the story reaches its climax, the main conflict gets resolved, the player tension - fully released, and the experience becomes whole. There might be some sort of cliffhanger foreshadowing more of the story: a sequel or any other continuation, and it will build up tension again and leave it without release. The ending can also be obscure or entirely open, which might also leave the player tense and guessing what the heck happened, but generally the main plotpoint gets resolved and the story - and the experience - take their final shape.

Sense of Progression

The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening

An invaluable tool that helps pacing and structure of any game is a sense of progression. If the player doesn't feel that they are moving forward at an acceptable pace, it can easily demoralize them and even cause them to quit the game for good. Here the balance is also very important: the game needs to reward the player for overcoming challenges and do it proportionately; too little might become demoralizing and too much can lead to devaluation. The type of reward depends entirely on the genre of the game and it's, let's say, marketing point. If it's some kind of narrative-heavy game, your progression might be marked by how much of the story you've learned and how close you are to the big reveal. If it is an RPG, you can add here new gear, new abilities and new areas to explore.

These components of pacing and structure do not only apply to the game - or a story - as a whole, but to its smallest parts as well. Every quest has a setup, confrontation and resolution, your every action has its own period of tension and period of release. These things can be scaled up to encompass your whole experience playing a 100-hour game - and scaled down to describe you picking mushrooms for a potion.

Let's slap this structure on any Hades run to see how it functions on a smaller scale.

Three-act structure in Hades runs

Setup

- A release stage - you run around the House of Hades, talk to the NPCs, learn more about the story and characters, which also works as your reward for the previous run.

- A tension stage - you adjust your stats in the Mirror of Night, choose your weapon, your aspect and your trinket according to how you want to play your next run and what new things you want to try.

Confrontation

You run from the Underworld through several regions. Every room has:

- A tension stage - the intense combat.

- A release stage - after the room is cleared, you get access to your reward and other side activities such as the Well of Charon.

Every region has:

- A tension period - rooms where you have to fight to progress.

- A release period - rooms with NPCs, Charon's Shop or fountain chambers where you don't have to fight and can catch your breath.

Resolution

As you reach the final boss, which is also the climax of your run, you have a final fight (a tension moment) and then, depending on the result, a release stage: either you proceed to the surface and don't have to fight any more, or you die and go back to the House of Hades. Both results discharge your tension and drop your action level back to zero.

You can have even more fun trying to apply the same structure not to the whole run but to a single region where you start in easier rooms that gradually become more challenging, reach your climax with a boss and then take respite as you transition to another region. Oh, Hades is good.

Since we have established what tension and release periods are and how their balance can affect the pacing of the game, let's finally talk about OMORI.

What is OMORI?

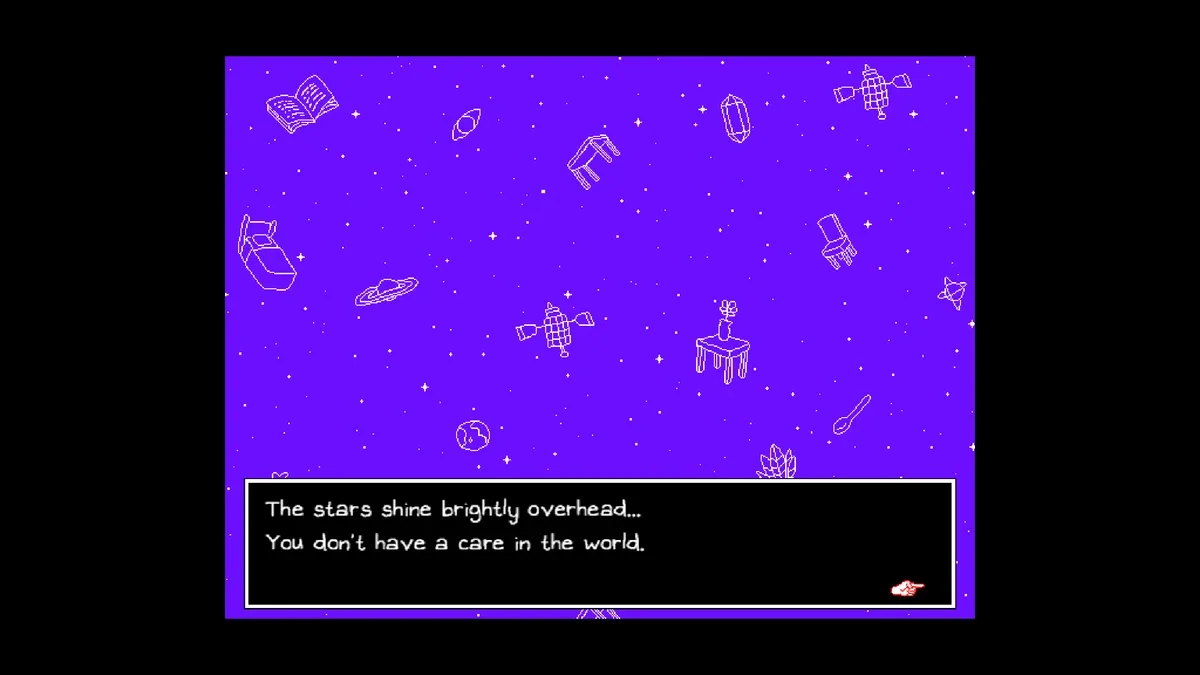

OMORI is a psychological horror with turn-based RPG combat that is focused on uncovering a mystery. The game alternates between two worlds: a colorful vibrant fantasy world that you explore with 12-year old OMORI and his friends, and a real world where 16-year old SUNNY is getting ready to move out of town.

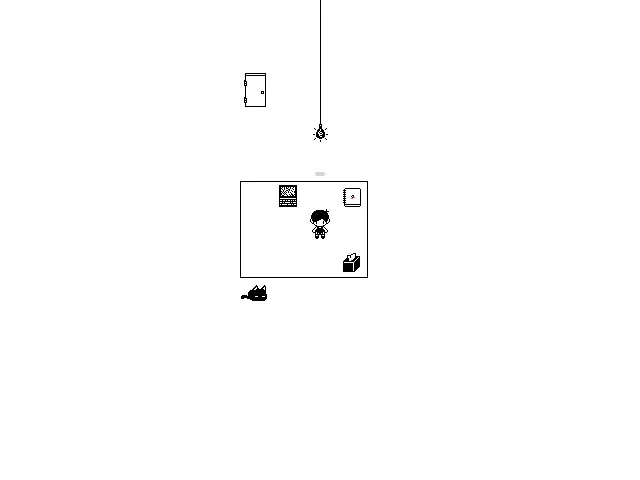

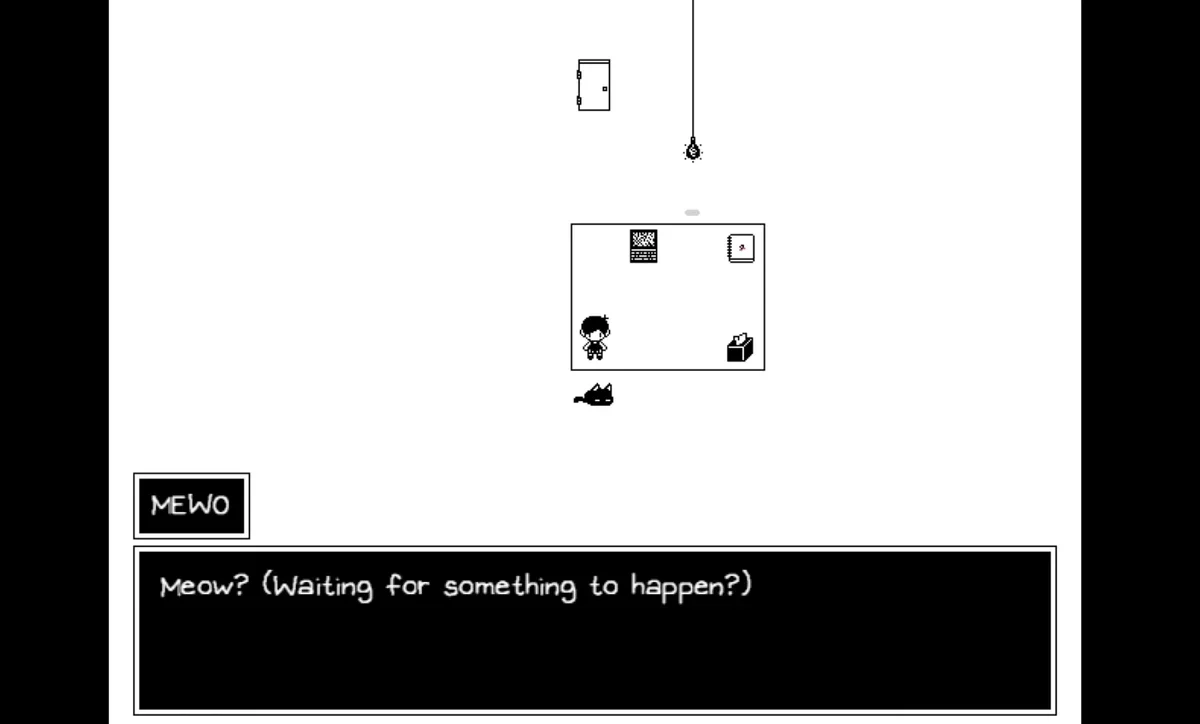

The setup stage in OMORI hits a little bump as soon as the game starts. You are introduced to a place called WHITESPACE that has a few items and a door that you for some reason can't open. When you've explored everything, you become kind of stuck because there doesn't seem to be a way to open the door, and you have already exhausted every interaction point. This was really discouraging for me as I wanted to jump into action but was stuck in a white room with the door that didn't seem to be openable. I was getting ready either to quit for good or just google the walkthrough when I finally found a way to get out. It was disappointing but then I thought that maybe it's just my problem and I am just slow.

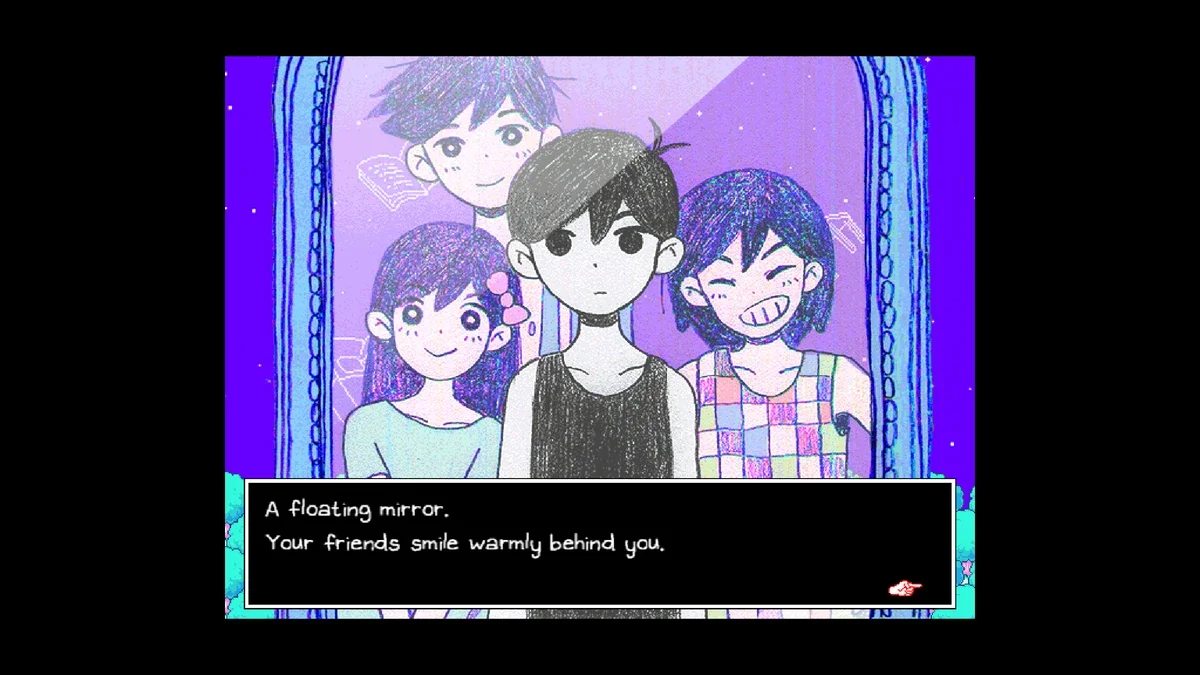

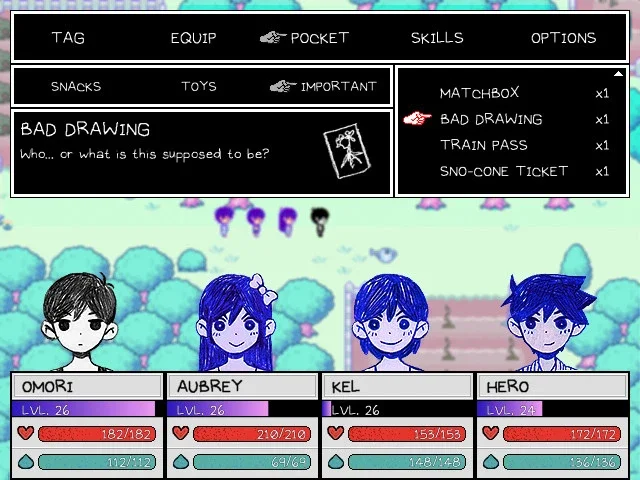

Then the setup unravels in the most amazing way possible. You meet OMORI's friends: AUBREY, a caring girl with a baseball bat that seems to have her heart in the right place; KEL, a hyperactive mischievous kid with a ball and his older brother HERO, a soft and responsible teenager who loves cooking. The artstyle makes you fall in love with these kids immediately, and you start caring for them the moment you memorize their names.

Later you meet MARI, OMORI's older sister about the same age as HERO. She is not a member of your party but her picnic blanket and basket act as a checkpoint. During the setup you explore the playground where you meet other children and learn how combat works.

Then you meet another boy called BASIL who is also OMORI's friend but seems to be an odd one out despite the fact that everybody loves and accepts him. You get invited to his house and learn that BASIL has a gardening talent and grows a lot of plants all over the place. As soon as you reach his house, the horror cutscene pulls a rug from under you as you see BASIL freaking out about a photo that he doesn't remember taking. The scene end very abruptly and you go back to WHITESPACE where you have no other option other than to stab yourself with a knife.

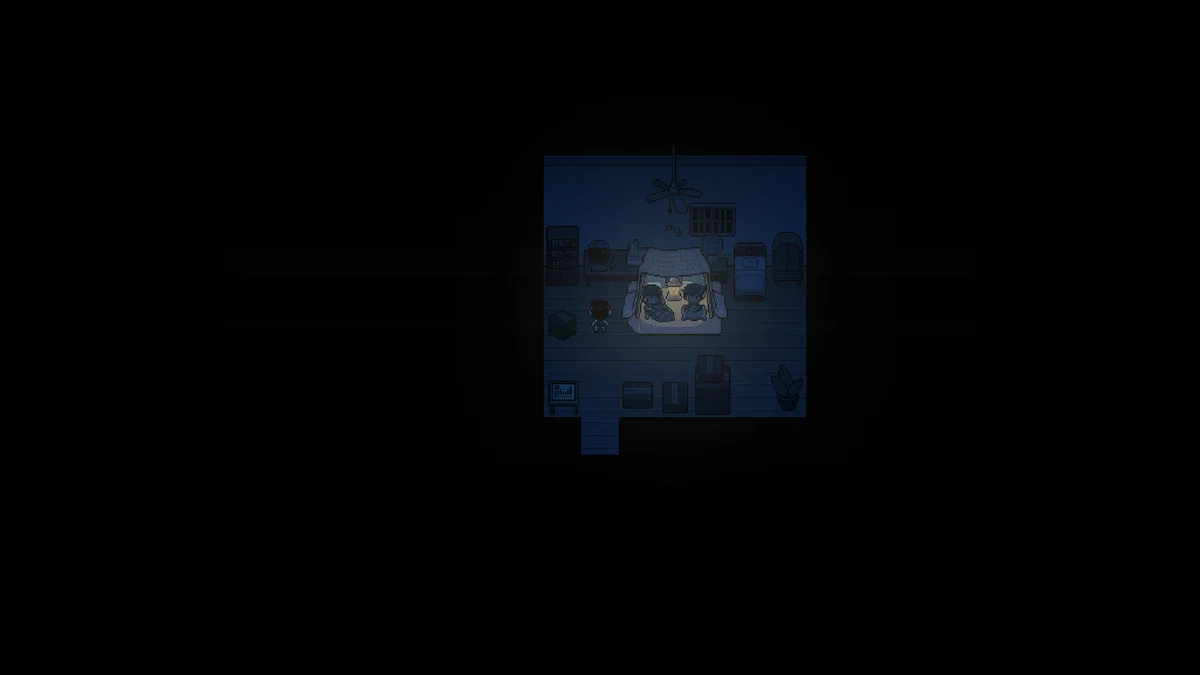

The screen cuts to black and you wake up in the real world as SUNNY.

It was A-M-A-Z-I-N-G. By that point I had already forgotten the door mishap in WHITESPACE. I was shaken to my core by the blinding contrast between the friendly fantasy world and the charming kids - and the horrifying cutscene with an evil monster that did something to BASIL who seemed a very sweet child, if a little shy. This was the inciting incident, the catalyst - something horrible happened to BASIL and now we have to learn why, find him and save him. I was completely engrossed: I was both in love with the characters and invested in the story and I was ready to use this impulse to carry me all the way to the credits.

It didn't work.

The Objective

In any game you usually have some long-term goal that looms on the horizon and reminds you what all your actions will gravitate towards at the end. It might be saving the world by defeating the final boss, it might be saving somebody, it might be obtaining resources, you get the idea. In OMORI your objective is The Story. Very early on you realize that something happened between the time in the fantasy world where the children are the best friends ever, and the time in the real world where they have grown older and hardly even interact anymore. And this Mysterious Event, or The Story, or Something That Happened, becomes your Objective. You need to learn what happened and why.

The problem, however, lies in the distribution of the story between two alternating worlds. Fantasy-world sections bulk up the majority of the playtime and hardly have anything to do with the story. Yes, you are searching for BASIL after he disappeared but there are hours upon hours of gameplay when you get zero information relevant to the main plot.

The real-world sections are your only hope to learn more but they are much shorter and give you half a fact at a time before you are thrown back into the fantasy world to do something that will not in any way help you uncover the story. Yes, after spending 5 hours in a castle resolving one character's plotline and battling your way through a hoard of sprout moles, you will probably get a line of dialogue that will tell you nothing definitive, or a hint that won't help you in any way.

Remember when I was talking about keeping the player tense all the time? This is what happens in OMORI. During the setup stage the game tells you: something has happened. You need to learn more.

You become tense.

And then there are hours upon hours of content that don't seem to have anything to do with uncovering the main plot.

You are still tense.

Then you get some kind of information but this reward is disproportionate to how much tension you've accumulated, and it leaves you frustrated. It just seems like bait and switch - the game got you super interested in something and then acts like it doesn't know what you're all riled up about by making you do unrelated things.

Game Pacing

I play a lot of RPGs and I think I have a general idea of what RPG progression is like. You start from lvl 1, then level up pretty quickly and then slow down as there is more experience needed for subsequent levels. In OMORI, for some reason, it works backwards. As you move through the game, you level up faster and faster, gain new skills every few battles and it quickly becomes overwhelming and hard to handle.

Every character in your party has a role and a pool of skills of which you have to pick 4 for your roaster that is available in battle. Combat in OMORI wasn't really for me and not because it's somehow bad or poorly designed - on the contrary, I find the emotions mechanic very interesting and fun - but because of a sheer amount of fighting in this game. You are constantly in a brawl, it's just exhausting. Lower level enemies would still engage you in lategame making you go through the motions by hitting ATTACK 4 times knowing that the enemy will be dead three times over after your first character strikes. Of course, you can try and run away, and that was what I did most of the time in late game, but it still takes time and you can't really skip all the fights because you need to level up to stand up against bosses.

As skills become too abundant too quickly, so do the trinkets that you start picking up more and more as you progress. It seemed to me like I had to manage my skills and trinkets every few battles because I got something new again and had to shake my whole party from top to bottom again. This reminded me of a game I played a long time ago where all drops were for my class and my class only. Sounds great but I had to open my inventory every minute to see if that item I picked up was somehow better than what I've got.

Side quests that you get are almost exclusively fetch quests where you have to run from point A to point B to deliver an item you got at point C. As you are running back and forth, you just get into more fights or have to spend time running away or around enemies.

NPCs, unfortunately, are not here to impress either: they don't have any meaningful lines or funny jokes, they don't add anything to the game other than populate the areas, but there are so many of them you just have no idea. I always talk to everybody not to miss out on a piece of information or a quest, but I swear, in OMORI you can skip every single NPC who is not marked as a quest giver and it will save you like 3 hours of playtime.

OMORI is way too long

This game is unbelievably long. Each episode could be cut in half and it would only improve game's pacing and structure. Later in the game I discovered Orange Oasis and instead of excitement I felt dread. I thought, "Oh my God, I will spend here the next four hours without learning anything new about the story, won't I". And yes, that's exactly what happened.

I struggle to understand why every scene in this game is stretched so far beyond any reasonable expectation. It's as if the developers thought that 6 years in development should mean 60 hours of gameplay. There is a section closer to endgame where you have one door per each letter in a sentence. That's like 20 doors! You take the key, open one door, have a small horror episode, find another key and walk out. Then you open the next door with this key, have another horror episode, find the key and walk out. 20 times or so. Yes, I believe after like a half of it you can progress further and ditch the doors but I didn't want to skip any story-related episodes and I certainly didn't want to get a bad ending just because I didn't finish 20 doors.

It is a good example of continuous horror tension that quickly devalues the horror. The first couple of rooms you are genuinely terrified but then you go "Yeah yeah, where's the damn key"?

And Then Comes The Flood

The game just pours the whole story on your head in the last ~1.5 hours. It is as if you have both confrontation and resolution slammed together and fit into a very small timeframe where everything starts finally making sense.

I want to make it very clear that The Story, that Thing That Happened, is absolutely tragic and soul-numbing when you learn the entirety of it. It actually makes your blood run cold. It touches on a lot of sensitive topics like anxiety, depression and trauma, but the game should've been much, much shorter for it to work perfectly. The story - however horrifyingly tragic and emotionally complicated it might be - is really short and quite straightforward, and yet it is fed to you a teaspoon an hour, it's just excruciating.

Conclusion

OMORI impressed me a great deal with its beautiful artstyle, immediately likeable main characters, wonderful music and an interesting combat system that I haven't seen before. However, the pacing and structure turned out to be the weakest parts of this game. It just has no proportions.

The setup is brilliant, perfectly timed, well-balanced, it grasps your attention almost immediately and the contrast between the scenes that transpire during the prologue just throws you into ice water.

And then the game just forgets it all and starts doing something else, leaving you with all this emotion completely helpless.

Since it's the story that is supposed to drive the gameplay of OMORI, I find it really bizarre that it is completely out of focus for the majority of the game. This tension that the game built up so successfully in the setup never gets to its release stage because the middle part - the confrontation - is basically non-existent. The long adventures you're going through are almost entirely unrelated to the story that you're supposed to uncover, and this fact forces you to perceive these adventures not as standalone functional parts of the game but as unnecessary obstacles that you have to overcome to clear your way towards your goal.

This player tension in the back of my mind led me to frustration and desensitization because I was so invested in this story but for hours I got nothing in return. I just became tired of all the unspent emotion. And then when it started blasting me like ocean waves I was very confused.

There is so much fighting and so little to do apart from that because the NPCs and quests hardly have any substance to them. You are either stuck in a long tension stage with fighting and skill management, or in the release section where you are just running errands and nothing of value happens. It could be bearable but it's all just made worse by this growing frustration that whatever you're doing will not help you move forward with the story and will not give you any information, and this frustration devalues many things that could otherwise be quite enjoyable like clever boss fights and exploration of the new areas.

It is quite interesting to observe similarities between the real world and fantasy world, items and phenomena transformed and distorted by the perception of the main character but it doesn't take much time to understand what is based on what and how items in the fantasy world connect to the items in the real world. The symbolism is also not that incredibly hard to follow, the resolution of the story sorts it all out very clearly, thus I cannot comprehend why the player is forced to spend so much time in the fantasy world where next to nothing of the story is ever revealed. It's almost like in the many years of making OMORI the developer came up with too many adventures and concepts and decided to keep them all whether they are directly related to the story, related partially or unrelated completely.

Yes, after you complete the game you kind of realize why it was how it was, but, honestly, t didn't bring me any peace. I wanted it all to make sense while I was playing and while I was in the moment, not after I finished. I think the game could have achieved exactly the same effect by being much shorter and a more concentrated experience overall.

OMORI has many wonderful elements to it, but at the same time for me it stood out as a curious example of a game that didn't work for me because of its pacing and structure.

Thank you for your time, and I'll see you in the next post. Take care.

Playtime - 28hrs